Hi, and welcome back. In the last issue, we looked at risk assessments and why our most serious injuries didn’t come from the most dangerous things we’ve done. Although this might seem counter-intuitive or at least counter to what your mother probably said, in a high shrill voice, a lot more than once, which was, “Don’t do that—it’s too dangerous,” or “You shouldn’t play that sport—it’s too dangerous,” or, “You shouldn’t go skydiving or scuba diving or anything in between…” and the reason that they think that “it’s too dangerous” is usually based on the amount (usually a lot) of potentially hazardous energy. E.g. “What if there are sharks where you’re going scuba diving?” vs. “What if you get complacent and run out of air…” and if they do include human error in their risk assessment (or warning), it is usually about the lack of training or experience. E.g. “You don’t know the trail well enough to go hiking by yourself.”

So, it’s understandable—or at least it’s very easy to understand why most people do not focus on the “human error” component or consider it to be the most important. We’ve been led in the wrong direction—for a long, long time—ever since we were little kids. Which is unfortunate. Because, as you can imagine, running out of air or some other form of human error is involved in over 95% of scuba diving fatalities (sharks don’t even get to one percent). Driver error is also over 95% of primary causation vs. weather, mechanical failure (brakes), etc. So, with all the statistics available, you’d think human error would have become a mandatory component in risk assessment! But that’s how strong some beliefs/paradigms are; they can get people to ignore statistics or worse, discount what has

actually happened to them.

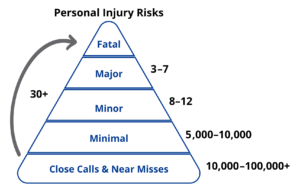

However, there are other paradigms, beliefs or perspectives besides this misconception of “danger” that are also

inaccurate. Ever since Heinrich, and then later Bird, we have been looking at risk pyramids. Conceptually, the idea

that there would be more close calls than minimal (firstaid) injuries; more minimal injuries than minor; more minor

than major and more major than fatal was totally plausible, it made sense and there were statistics to prove it. But the next part, that the only difference between minimal and minor, or minor vs. major was just luck—provided the overall amount of hazardous energy stayed the same — wasn’t questioned or challenged very much. But this line of thinking ignores the basic tenant, the number one piece of safety knowledge we do possess, that we know for sure— and that is: nobody—not you, not me, not anybody else— is every trying to get hurt! Which means we will also try very hard, even if it’s just a reflex, to avoid getting hit, or falling down or banging our head or crashing the car, etc., etc. In other words, we are not totally defenseless.

We negotiate hundreds or thousands of hazards every week getting to and from work, and what this article is about is that the difference between minimal and major isn’t luck, that there is indeed an assignable cause—even for most

of the ones that tend to get called “fluke accidents”. So, to help get to the bottom of all this, let’s go back to what has happened to us: Our personal risk pyramid.

We’ve all had 5-10,000 cuts, bruises, bumps and scrapes but most of us only had 5-10 or so that were serious, or if

we were at work, would be called a “recordable” injury. At 1000:1 we should be looking for an assignable cause vs.

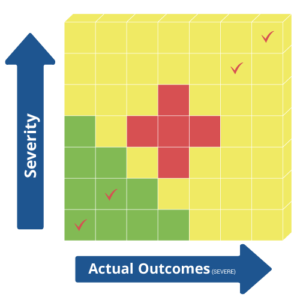

random chance or pure luck. But that’s not what happened. Instead, it seemed that popular thinking went in the other direction, giving luck even more credit, by calling some of them “fluke accidents”. Most people call two types of “extremely unlikely” events fluke accidents. The first is just a very unlikely occurrence—like getting hit in the head by a meteorite. The other is a very uncommon outcome from a very common occurrence— like someone losing their balance, falling backwards, hitting their head and never getting up again. If you think of the old risk matrix these would be in the bottom left hand corner which, ironically, is usually colored green.

When we look at all of the serious incidents and where the majority of them occurred, which is in the middle of the

matrix (see Figure #1—Actual Outcomes) there are some interesting patterns or similarities in terms of contributing

factors. First of all, we need to keep in mind that over 95% of these are in the “Self-Area” discussed in the previous two articles. And, as mentioned in the last article, eyes not on task and mind not on task by themselves cause problems, but we really didn’t talk about what happens if both errors are made at the same time. So, to help

illustrate the importance of each and then when both of them occur together—think back to the personal risk

pyramid or to what’s actually happened to you (see Figure #2 for reference).

Can you think of even one time (not including sports) when you’ve been hurt when you were thinking about what you

were doing, and the risk of what you were doing at the exact instant when you got hurt? Chances are, even if you

rack your brain, it’s hard to think of even one example—if it was in the Self-Area. And that’s true for almost everybody. It’s even true for a very high percentage of sports injuries. So, when it comes to getting hurt or not getting hurt, regardless of what you are doing (unless you’re not moving or nothing around you is moving) paying attention or not paying attention will be the most important, deciding factor. Of course, there may always be issues with training or skill, but since mind not on task is involved in over 95% of all injuries—whether they be serious, minor or minimal—that, more than anything else, has been the deciding factor in our lives so far.

EYES NOT ON TASK

Okay, so mind on task or mind not on task is king. But how important is the next critical error: eyes not on task? For this you need to think about all the serious injuries you’ve sustained (where the unexpected event was in the Self-Area). When you got hurt badly, were you looking at what you were doing? Could you see where you were going?

And did you look for what could be coming at you (lineof- fire), or what could cause you to lose your balance,

traction or grip? In other words, did you have your eyes on task—or not? For most people, the majority of their

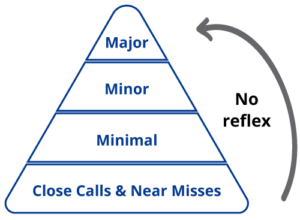

serious injuries happened when they made both critical errors at the same time. They weren’t thinking about what

they were doing and at least for a moment, they weren’t looking either. And when you’re not looking and you’re

not thinking—unfortunately, you won’t get the benefit of your reflexes. And yet reflexes can easily be the difference between a near miss or a fatality. So, when you think about it, how often have your reflexes prevented an incident or accidental injury? How many times have you had to hit the brakes suddenly or jerk the steering wheel to avoid hitting another car, truck or pedestrian? How many times have you regained your balance without actually falling? Hundreds,thousands? One thing is for sure: it’s far too many to even begin to count.

Thankfully most of us can count all our serious injuries. So, when you think about the stitches, broken bones,

concussions, serious burns, etc. did you get the benefit of your reflexes? (See Figure #2) Because if you didn’t see it or see it coming, then you probably didn’t get a chance to hit the brake, jerk the steering wheel, duck your head, get a hand down to brake your fall, etc. So instead of a glancing blow, it’s a direct hit and stitches or a concussion. Instead of it being another embarrassing fall, it’s a broken hip and instead of it being a fender bender, it’s a head on collision, or instead of a quick step to the side, somebody gets run over when the operator is backing up with a piece of mobile equipment.

So, both critical errors: eyes not on task and mind not on task are involved in a very high percentage of all serious injuries whether they are at work, at home, in the community or on the road. Which makes sense, since we are never trying to get hurt anywhere. So, if we could improve people’s skills and habits with eyes on task that would improve the likelihood that they would get a reflex, and that, in most cases, would be enough to prevent a serious injury. It might not prevent the incident from happening in the first place, but reflexes do a great job of keeping it from being more severe (see Figure #3).

What this also means is that almost all serious accidents of this kind can be prevented if we can get people to improve their habits with eyes on task. For example: looking for things that could cause you to lose your balance, traction or grip, looking for line-of-fire potential before moving, looking up before you stand up to avoid banging your head and moving your eyes before you move your body, feet, hands or car (vehicle), etc. And while good habits

can compensate for complacency leading to mind not on task, they don’t prevent it. That’s impossible—if you

know how to do something well (more on that later). But there are other critical error reduction techniques that will help to get your mind back on task if you’ve drifted off or start driving/working on autopilot. And if you add enough rushing, frustration or fatigue to the equation, those states can override good habits (a driver in a rush doesn’t look over shoulder before changing lanes) which means we will need more than just improved safety-related habits to deal with all four states.

In total, there are four critical error reduction techniques people need to know and use to prevent critical errors. But for now, the main paradigm shift is that mind not on task is a contributing factor in over 95% of all injuries and that for a very high percentage of the serious injuries, eyes not on task was also a contributing factor, which is why we didn’t get the benefit of our reflexes, which is why the injury was so uncommonly severe, or so seemingly unlucky—that is gets called a fluke accident.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE!