Thanks for coming back to the last article and final paradigm shift. In the last issue, we looked at just how many errors are caused—every day—by rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency. Although usually it’s a combination of these states, with complacency either leading the way or lurking in the background. And we have also looked at how the four states or a combination of them can cause problems—lots of problems—with decision making. For example: suppose a job or even a big “turnaround” is running behind schedule. People are rushing or going faster than they would normally go. As a result, some safety devices, procedures or protocols—like doing a risk assessment—that take time, are very tempting to avoid or bypass. Yes, the people could self-trigger on the rushing, come back to the moment, and realize that their decisions are being compromised because of the rushing. But why were they rushing in the first place? And this brings us to the final paradigm shift.

Why do people, why do we all—rush? And remember, this simply has to be “going faster than you normally go”. It doesn’t have to be for long, it can just be a quick turn without looking—and it doesn’t have to be at recordbreaking speed either. It’s just going faster than you normally go. And it happens to all of us, every day, with very few exceptions. However, when you ask, “What causes most people to rush?” almost everybody answers, “Poor planning”. But have you ever planned to rush? Not likely, it’s unpleasant and stressful. Very few people say, “Let’s just stay here and have another coffee. That way, when we get to the airport, we can plead with everyone in line to let us cut in. Then we can run down the hall in our business clothes, dragging our roller bags so we can get on the plane just in time to sit down—soaked in our own sweat—saying, ‘Yes, this is just the way we planned it!’” But if you realize that you forgot your laptop half way to the airport and now you have to go back home or to the office to get it—now, you will be rushing!

Now you will be pleading with everyone in line to clear security, you will be running down the hallway dragging your roller bag, sitting in your seat soaked in sweat. And it’s no different for the welder or tradesperson who gets out to the job and realizes that they have forgotten to bring the right weld rods or the right tools and they have to go back to the tool crib or maintenance shop. If everybody’s waiting and the line is down, the personal motivation to rush will be extremely high. And that rushing could easily cause more performance errors or worse, an injurycausing error like a loss of balance, traction or grip going down the stairs or around a corner.

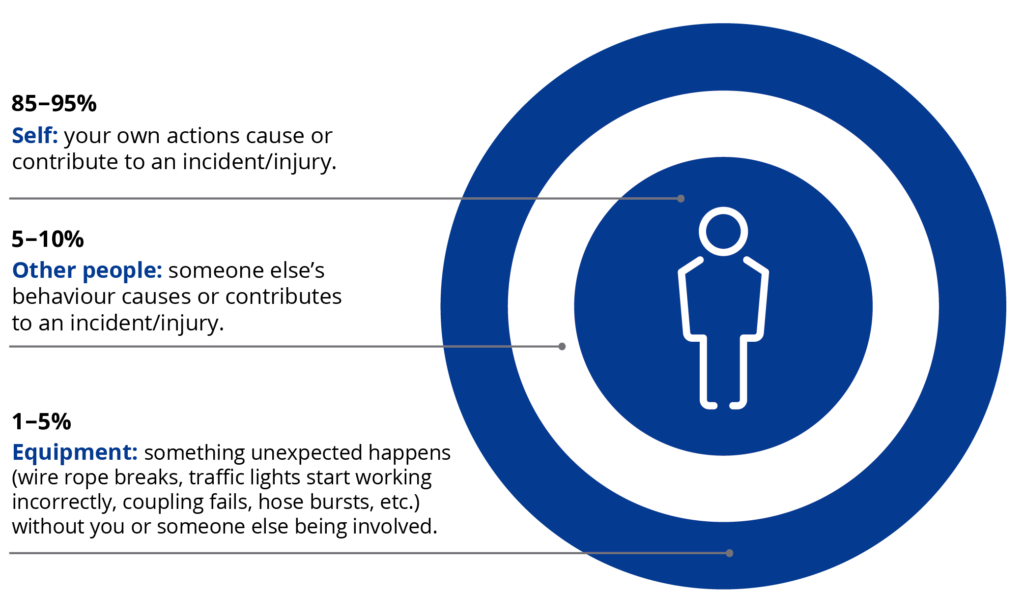

The point is: it’s not all poor planning. To put it into perspective, there are essentially only three (familiar) reasons why people rush (See Figure #1—Three Sources of Unexpected Events).

1. They do something that makes them rush (make up time for performance error or poor planning)

2. Someone else does something that makes them rush (their performance error or poor planning)

3. The environment does something that makes them rush (traffic jam, equipment breakdown, etc.)

If we look at the environment or the situation causing us to rush—unexpectedly—it does happen. However, if you don’t even look at an App/GPS to see if there might be a traffic jam— because its normally fine at this hour—then arguably, its back in the “self-area” with complacency being the dominant state.

In a similar sense, other people can also make us rush unexpectedly. But if someone is always late then it’s not entirely unexpected. It might be frustrating, but it’s not unexpected. Which is why you tell your mother in law or father in law that dinner is half an hour earlier then you will actually be serving it. In other words, because they are “predictable” you can plan around it. For the people who are “unexpectedly” making you rush: why are they doing it? Chances are, they are also rushing partly because they know you are waiting. Well, it could have been their poor planning or it could be because they made a mistake that cost them—and now you—some time. Maybe they forgot something and they had to go back to get it or maybe they couldn’t find something and that’s why they weren’t ready on time. But if this person (or group of people) is normally on time, you can bet that they didn’t plan on being late. Much more likely that they made a mistake and that’s what’s causing them to rush.

When you look at it from the perspective of the 3 sources of unexpected events, most people freely admit that over 90% of the reasons they rush are in the “Self-Area”. And as we’ve already discussed, we never plan to rush. So, what this means is that approximately 90-95% of the reasons we rush are to make up time for performance errors we’ve made—when we weren’t learning anything new. And you can say all you want about “poor planning” or “good planning” but nobody leaves an extra hour every time they go to the airport or leaves for work an extra 30 minutes early just in case they realize when they’re half way there that they forgot their laptop. It’s too inefficient. Carry two laptops with you—at all times? That’s a lot of extra weight.

So, we hope or count on our own reliability, which usually isn’t so bad. But every now and then, we make a mistake and that mistake can cause us to rush to make up for the time we just wasted—even if it’s just going to the car and realizing that you forgot your phone— watch how much faster you move when you go back in to get it. These kinds of mistakes cause wasted time, so we’re inclined to rush a bit to try to make up for it. However, if it’s a big error, like you forgot the 90-degree elbow for the drain pipes and the cement truck is pulling up to the construction site—and the superintendent is coming by after lunch… Now how fast will the supervisor be driving back to the shop or hardware store?

The inclination to rush would be enormous. I asked this question “hypothetically” to one of our consultants who used to work in residential construction “How fast would you be driving to the hardware store to get the elbow?” He answered, “I got clocked in going 85 (mph). But the cop let me off when I told him what happened” which is also interesting: “Production, or I did it for production”- seems to be a really good excuse, too¹. But I was only asking a hypothetical question, I didn’t know he’d actually done this. However, it proves the point: mistakes are really what causes people to rush. Most of the time the reason we’re rushing is because we are running late. And the reason we’re running late isn’t because we planned to rush. Something unexpected happened. But over 90% of that is in the “self-area”. In other words, we caused it. Since it’s unlikely we planned it, what’s left… is human error. We made a mistake. Not every mistake we make wastes time: some just waste money or emotions, but most of them do waste at least a bit of time. Considering how many mistakes people make on a daily basis, it’s no wonder that we find ourselves rushing so often. And yet, we always seem so surprised when it happens, “I can’t believe I’m doing this again” (running down the hallway at an airport), because we certainly didn’t plan it that way.

ENGAGEMENT

We have all heard the expression: knowledge is power. But unless that knowledge is put into action, the amount of power is fairly limited, or—more likely—will be “proportional” to the amount of action or change in behaviour the knowledge provides. When it comes to preventing “defenseless moments” we have to get people to develop or improve their skills like self-triggering and they need to change some safety-related habits like moving their eyes first, before they move their hands, head, body or vehicle. But if they know about the 4 states and critical errors they can also anticipate when they will likely be rushed, frustrated, tired or be complacent/go on auto-pilot. And most of us can also predict or anticipate what the most expensive mistake would be, or the most time consuming. If we are thinking about these mistakes or about not making one of these mistakes—then, in almost all cases—we won’t make one because we’re thinking about it.

However, just because we can predict or anticipate the states and the worst-case scenarios doesn’t mean we will. Without the knowledge people can’t change because they don’t know what to do, but rarely that is enough. People need to be engaged. This requires contact and communication that is both relevant and efficient. So, while I wouldn’t call this part of the article a paradigm shift, it is definitely a different way of looking at engagement. I spent the first 15 years of this career teaching people how to make positive, meaningful safety observations. The engagement centred around what just happened and the behaviours that were observed. With behavioural safety observations you are discussing what the employee was just doing, with the idea being that you could correct at-risk behaviour and reinforce safe behaviour, so that safety-related behaviour in the future would improve. It might seem relevant— since you were just watching them work—but it’s still in the past. And the feedback in this process tends to be centred around things like PPE, procedures, rules, etc. So, it’s more useful for decisions than it is for preventing errors or critical errors in the future, partially because that’s not what is usually discussed. Furthermore, watching people work is somewhat invasive, and depending on the size of the site and where people are working, sometimes it’s not very efficient either.

Getting out and talking with people about potential errors they could make in the future is easy—you don’t have to observe them working—you can talk to them almost anywhere. And it’s not invasive since you are only talking about what could happen, not what just did. But most importantly, it gets them thinking about the states that could lead to critical errors and serious mistakes—which will help them self-trigger much more quickly—if the states they predicted and the errors they anticipated start happening. And as soon as they self-trigger or come back to the moment, the less likely they are to experience a critical error or to make a serious mistake. So focusing the engagement on the future: what could happen and what states would likely cause it is pro-active and relevant, because it gets them thinking about what “could happen” instead of what “just happened” and it gets them thinking about the states that could cause a critical error or combination of critical errors.

Then, once they identify the states the next step or question is when. When will they or me or you likely be in one of those states? You know when you’ll likely be rushing or tired. So just before that time you can set an alarm to Rate Your State™ For example: if you know you’ll be rushing just around shift change, you can set an alarm to Rate Your State™ a few minutes before, so you can remind yourself about the rushing and self-trigger more quickly. Simple tools, that anyone can use, that are very effective in terms on preventing critical errors in the future. And so easy too, in terms of meaningful and totally voluntary engagement. Not sure why I didn’t see this earlier, maybe focusing too much on the present or what the employee was just doing. But it’s really such a simple shift: just focus on the future and get people thinking about what could happen, not so much about what just happened. This makes it so much easier to get people talking, not to mention organize and administrate. But it also makes it much more relevant because it gets people thinking pro-actively about preventing the next big one…

CONCLUSION AND SUMMARY

Well, first of all, thanks for coming this far. Let’s face it: not every book gets read till the end. And for the people reading these paradigm shifts as they’re released in magazines—despite their best intentions—it’s easy to imagine a number of things happening that could prevent someone from getting the final issue. So, thanks again for coming this far. But if you think about it, we have covered a lot of ground in these 12 articles.

So now, if someone asks you, “Why do people rush?” Or, “What causes unintentional injuries?” Hopefully you’re not going to say, “poor planning” or “hazards”. Whether you want to explain all these paradigm shifts is up to you. It would require getting them to think about hazardous energy which kinetic energy, the three sources of unexpected events, why the most dangerous things didn’t cause our worst injuries, the critical errors and “defenseless moments”, the neuroscience behind complacency, how the four states can compromise decision making and factoring out the “when you were learning” mistakes. Not exactly the kind of thing you can do in an elevator. Maybe it would be easier to say, “rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency.” Or, if it’s a really short ride—just say, “human error”.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE!