Last issue we looked at the complacency continuum and the importance of “when” vs. “what”. (Please see Figure #1). When did you get hurt vs. what were you doing? And if you really think about it or if you really think about what has actually happened to you, you’ll realize that you have most likely experienced accidental pain—even if it wasn’t serious—in almost any activity you’ve ever done, whether it’s walking, running, cleaning, carrying something and dropping it on your foot, cutting, hammering, driving, cooking, sewing (you name it), chances are—you’ve said, “Ouch” or something worse—more than once. So, if you can accept that the “what” isn’t really where the pattern is, because, we’ve all been hurt, a little or a lot, doing pretty much everything (as long as you were moving and/or things around you were moving). So, the pattern, especially in terms of our serious injuries, has been when we made both of the first two critical errors at the same time: we didn’t have our eyes on task and we weren’t thinking about what we were doing (mind not on task). And as a result, we didn’t get a reflex—which might have enabled us to hit the brake, jerk the steering wheel, catch our balance or break our fall, move our head quickly, etc.

So, we looked at the problem of figuring out “when” in the last article. When would we or when would they be most likely to have those “defenceless moments”? The conclusion was that they (at least the majority of them) would happen after the first stage of complacency, and—although the person wouldn’t likely know it—be happening more frequently as they passed into stage 2. Which helped to answer the question of why older, well-trained workers, with lots of experience were experiencing so many serious injuries and fatalities. Note: before the first stage of complacency, untrained workers or workers without enough experience do get hurt frequently. But they are usually more mindful in terms of paying attention. They just don’t have the skills or reflexes yet. So, that’s easy to understand and it’s easy enough to fix, if you’re willing to take the time to train them properly.

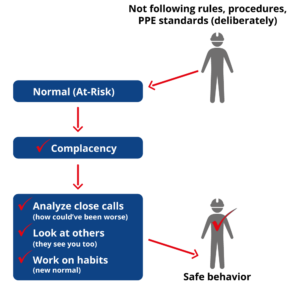

However, there’s more to it than just that. As mentioned, albeit briefly, in the last article, as time goes on people tend to get more complacent, not less. The increased level of complacency can also start to affect someone’s decision making. Not only do they have more “defenceless moments”, but if nothing bad has actually happened (vs. just another close call) then the person’s willingness to change will be very low, and certainly their belief that their behaviour “really needs to change” will be virtually non-existent. Hence the: “Oh yeah, well I’ve been doing it this way for 20 years and I’ve never been hurt yet!” So, for them, “normal” behaviour is “at-risk”. In other words, they normally don’t wear the face shield at the grinding wheel or they normally don’t wear a seat belt on the fork truck. And if someone’s been using the grinding wheel without a face shield for 20 years, we can assume—with a fair bit of confidence—that complacency has gotten the better of them.

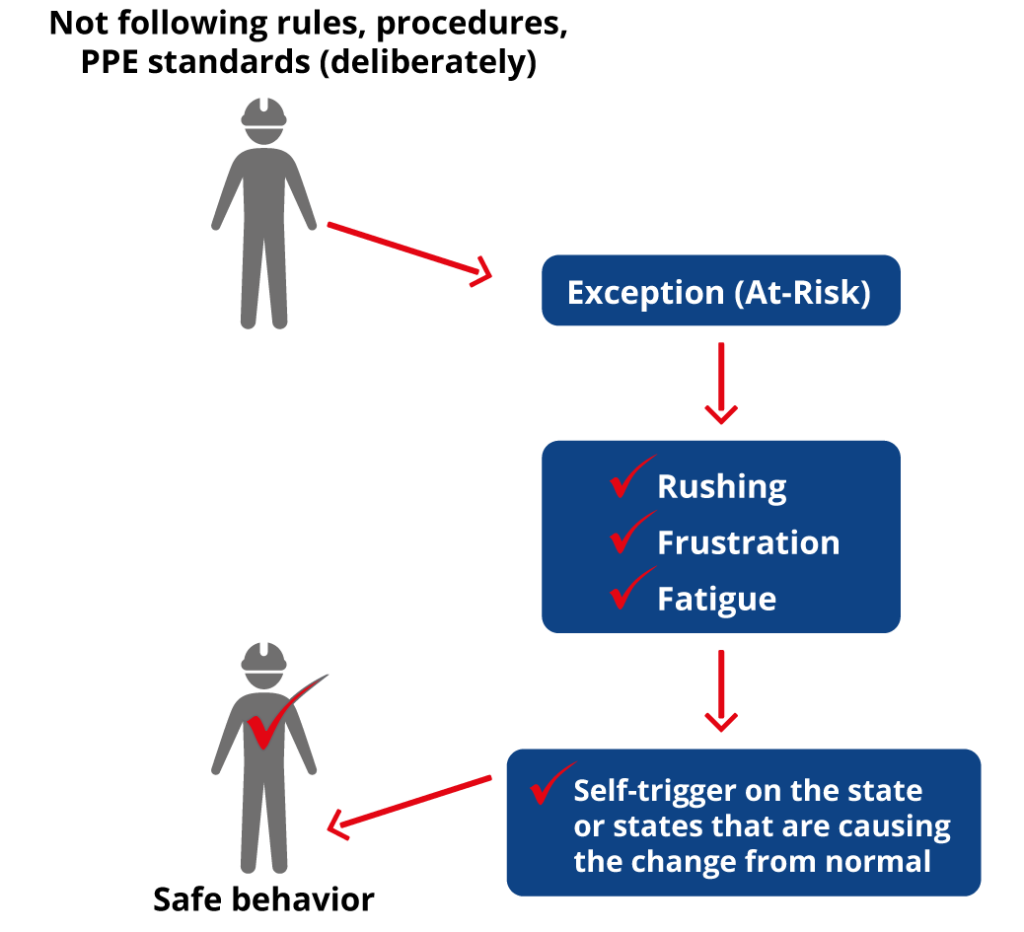

Then on the other side (see Figure #1), there are people whose normal behaviour is safe: they normally do wear the face shield. Just like people normally drive the speed limit or maybe a little above the posted speed limit. In other words, you know what you mean when you say, “I was driving at normal speed or at a normal speed for me—given the conditions”. Let’s just call it, “our own speed limit” which—as mentioned—might be slightly higher than the posted speed limit. But here’s the thing or the main point: we have all exceeded our own speed limit when we were in a “big rush”. So, if we are in enough of a rush, we will make an exception, and not only break government laws or company rules, we will even break our own rules. And the same thing can be true for frustration and fatigue. Normal people can and will make exceptions or can have their decisions compromised by rushing, frustration and fatigue.

I can remember when this paradigm shift hit me. I was in Houston doing a 3-day workshop. Our video crew lives in the greater Houston area so we got together after day one to look at some of the “Tool Box” videos for a series they started working on. Although the manager of the crew was very familiar with the concepts and critical error reduction techniques, the crew really only knew about rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency. What I didn’t know (long story) was that the manager was not going with the crew to these shoots, so they were just asking for stories—true stories—that were about workplace injuries caused by rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency.

After saying hello and all that, they showed me the first video. It’s about a guy who has to cut a piece of pipe but the area or vessel he is working in at this power plant is too small to use the cutting disk he has. It’s 5:00 and the tool crib is a good 10 to 15 minutes’ walk away. Plus, he doesn’t want to put in for overtime, so he just “decides” to take the guard off. Unfortunately, there was a kick-back. The cutting wheel went across the top of his other hand, slicing almost all of the tendons. This wasn’t an error caused by rushing, frustration, fatigue or complacency. This was a decision that was compromised or negatively influenced by the combination of rushing, frustration and fatigue combined with his level of complacency. He’s very comfortable using cutting wheels after all this time and obviously, he’s confident enough with his skill level to think he can do it without the guard on. If you then add some rushing, frustration and fatigue to that level or that much complacency, what we find is that normal people—good workers—make exceptions and break not just government rules or company rules—they and we also break our own rules.

Prior to seeing the video, it just never occurred to me even though I had—no doubt—broken countless rules in the past because of rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency. And, for me, it was a big “shift” because I knew decisions, especially bad decisions about increasing the speed or force or not using or thinking about protection or protective devices was a problem. I didn’t think it was all about attitude—or “bad apples”—workers who vocally resisted using PPE or following rules, procedures, protocols or standards. And when I saw the toolbox video they made, it all just hit me.

It was so obvious. These folks just let rushing, frustration or fatigue get the better of them. Just like the guy who’s been doing it for 20 years has let complacency get the better of him. Normal people, who aren’t really any different from anybody else making critical decisions that are confirmed or negatively influenced by rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency.

However, it’s not hopeless. Since we know the state or states that are driving the behaviour—then, if we extend the concept or application—we can use the same critical error reduction techniques to prevent making a (compromised) decision that was caused by one or more of the four states. If we go back to the cutting wheel and the sliced tendons, the only reason he changed his normal behaviour and took the guard off was because of fatigue, frustration and maybe a bit of rushing. If he had self-triggered on the fatigue (most dominant) or the frustration and came back to the moment and thought about what he was doing—right now—and the potential for a critical error like line-of-fire then he could have at least stopped, thought about it and asked himself, “Is it worth it?” At least if he or you or me—if we can self-trigger to give ourselves a chance to see the real risk vs. being so preoccupied with the states that we don’t even stop and think… that will be a huge help.

About 10 years ago, I worked with a lineman who had lost his right arm and right kidney in an electrical contact incident. He told me pretty much that he really couldn’t understand it until he put the states and errors together. Then, as he said, “It was all so easy”. Just a simple, almost classic, state to error risk pattern.

I can also remember listening to Joe Tantarelli, a residential construction supervisor, telling the crowd how he got buried alive when the end wall let go and caved in. He was critically injured. He managed to survive though, and although it took a long time and a lot of physiotherapy, he’s walking and talking and speaking to audiences all over North America. “Joe Dirt” is his stage name. As part of his presentation, he talks about going to safety conferences after he recovered to try to understand how this could have happened to him. He certainly didn’t know why himself.

He knew he wasn’t perfect but he had always stressed the importance of safety with all of his crews, over all of those years… So, he couldn’t really understand it until he went to a session where he was introduced to the four states, and four critical errors. That’s when he made the connection to complacency and how the other three states caused so many problems with his decision-making that day; and how the combination of those four states contributed to him making the first two critical errors at the same time, and as a result, how that led to him getting caught in the line-of-fire.

The lineman that lost his right arm and kidney was rushing so they could finish their card game before the weekend. As he said, “If I had just stopped for a second and thought about it, you know—what could go wrong or what’s the worst thing that could happen—it never would’ve happened”. So, for exceptional behaviour caused by rushing, frustration, fatigue or a combination of those states, we can extend the application of the self-triggering technique to the decisions that are negatively influenced or compromised by those states (see Figure #1, right-hand side).

On the left side (See Figure #3) is the person whose normal behaviour is at-risk. For this person, we need to get them to re-analyse some of these close calls and think about how they could’ve been worse. That should help to “rock the complacency boat” a bit. Then we need to look at the third critical error reduction technique, which is “Observe others for state to error risk patterns”. Only in this case, we need to get the person to realize that, “other people see you too”. And if they see you at the grinding wheel without a face shield, what will that do to their level of complacency? And finally, the last technique: we have to get the person to wear the face shield until it becomes a habit. Then, just like when you don’t have a seat belt on in the car, he or she will feel uncomfortable if they aren’t wearing it. And once this happens, they won’t be fighting it or questioning their decision very much.

And for the person or people who has let complacency get the better of them (Figure #3), they need to slightly extend the application of the other techniques: think about how the close calls could’ve been worse, realize others see you, and work on the behaviour until it becomes the new normal.

You have progressive discipline for the problem employees. And you don’t need to do anything for the perfect employees (except there aren’t any). But normal people do make compromised decisions—on a regular basis—because of rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency or a combination of those states. And rarely, were they aware of just how much one or more of the four states was influencing them in the moment.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE!